Cigarette Cards, Trade Cards, and Trading Cards… what are they?

Welcome and thanks for visiting the CSGB website! This page is for those new to card collecting, or those wishing to expand their knowledge on the history of cartophily, the hobby of collecting cards.

You may already have read a little about the Cartophilic Society, but what exactly are the cards that we collect and how did they come to be? Let's explore this a little and talk about the origins of the cards themselves and how they have changed over time in both form and function to become what today we often call ‘trading cards’.

We'll start by looking at some early ‘tradesmen’s cards’, issued nearly 300 years ago, and talk about the development of the ‘trade card’. We'll then explore the development of the specific type of card known as the ‘Cigarette or Tobacco Card’ during end of the 19th Century, before concluding with the cards issued between the end of World War 2 and the present day.

A few key subjects are not covered here, such as developments in printing methods, the social and business history of trade cards, Victorian scraps, baseball cards, silks... the list goes on! However, if you are interested in the history of cards, explore our book shop, contact us with questions, or become a CSGB member and borrow a book from our library!

The Birth of the Trade Card

Collectable cards as we know them today have a history dating back to the mid to late 19th century with the earliest datable cards being issued in the 1870s. However, to understand the difference between trade cards, cigarette cards and trading cards we shall go back a little further and start by looking at their precursors over 150 years earlier. It’s perhaps worth saying at this point that although cards have been issued across the world, the examples referred to here will focus primarily on Europe and North America.

Some of the first examples were issued in 18th century London (with the earliest dating back even earlier to c.1630!). Although London doesn’t necessarily reflect worldwide attitudes to advertising, the examples that appear around this time are almost certainly reflective of a problem common to many businesses around the world: the need to provide a means of advertising a product or service and to direct potential customers to their premises.

Many properties in 18th century London simply had hanging signs as opposed to numbers as we see today. The furniture store founder Sir Ambrose Heal, who researched early trade cards, said that at a time where potential clients were often not fully literate, it was these trade signs that would be depicted on tradesmen’s cards or bill headings, serving as a visual reminder of the address of the establishment (Heal, 1925:3). However, from around 1718, hanging signs began to be removed (Malcolm, 1810:394-395) and from around 1762 numbering was considered the norm of property identification. The last streets in London to keep their signs were Wood Street and Whitecross Street, but they too were removed in 1773 (Heal, 1925:15). It’s possible to see when looking at early examples of these cards that as these signs fell out of use, the designs often included more elaborate and ornamented representations of the shopkeeper’s wares’ (ibid)

As time progressed, designs became more elaborate, and early trade cards utilised increasingly talented artists to raise the design quality. The image above shows a trade card design by William Hogarth (the noted painter and sketch satirist) for a Richard Hand, a baker and 'Chelsey Bunn Maker'. The function was to attract custom and, especially, the patronage of the wealthy. Even Chimney Sweeps and Nightmen (collectors of night soil) often produced stylish illustrated cards (see the Bodleian Library publication A Nation of Shopkeepers (2001) and the image below). These cards were beginning to move away from what Heal called the "straightforward announcement of wares" or a utilitarian picture of a hanging sign to remind people what to look for in the street and were arguably beginning to utilise what we might today call 'brand development and association', with artists creating grand designs for even the most humble profession.

However, a crucial consideration for cartophily is that these early examples were not made to be collected. That is not to say men such as Samuel Pepys didn’t keep collections of them, but they were not inserted into commercial products, nor numbered or grouped in any way to urge members of the public to seek out specific examples. To call these early issues advertising or trade cards may be widely accepted, but it was very rare for them to be stiffened in any way and the reinforced variety on pasteboard were almost exclusively a Victorian phenomenon (Heal cites only two examples as early as 1780 that had been stiffened (1925:1)). Though not cards in the traditional sense of the word, they are almost certainly the direct ancestor of the 19th century pasteboard trade cards.

The Victorian Trade Card

The 19th century saw key developments in printing methods. The invention of the chromolithographic printing method by Alois Senefelder in 1801 was critical in initiating the (albeit slow) shift away from the black and white wood cut and letterpress cards that had come before. In England especially, advertising cards were still seen by many as prestige items and so engraving was preferred (Bodleian, 2001). Lithography flourished in the USA however. Its first recorded use was for sheet music in 1820, but printing in large quantities was not seen until 1840 (Burdick 1960:3).

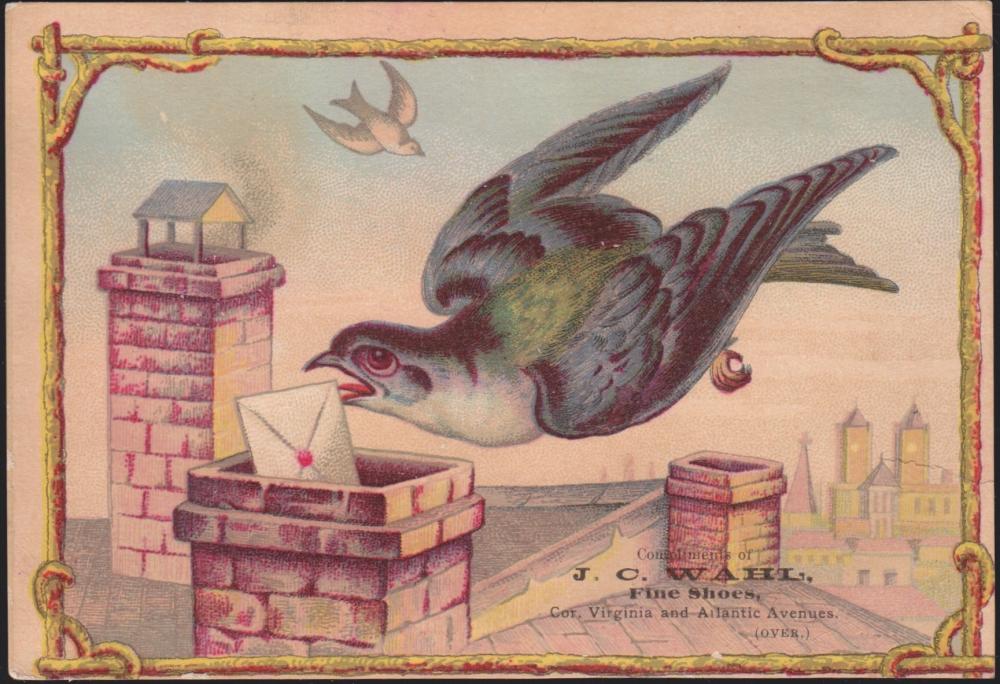

Where in the 18th century we saw heraldic devices and directions to shops, the 19th century saw a crucial shift in the way cards were consumed by the recipients/collectors. Cards were no longer constrained to simply telling a potential customer about premises and products. Companies began to use imagery on their cards that had little to do with their wares, but which focused instead on creating an attractive image that people would want to keep. A shoe maker might choose an image of a bird or a rural landscape - see the example here. This shift reflects the way that cards captured the public imagination, as well as the social context of the time. Laird (2001:62) tells us that:

in a culture not yet saturated with manufactured images, this accessibility evoked widespread excitement and acquisitiveness, and particularly when pictures were free because they carried advertisements

Perhaps it was only a matter of time, but towards the end of the 19th century companies started to issue ‘insert’ cards. Although these were still trade cards, their mechanism of delivery was significant: they were inserted into packets of a particular product in order to encourage further sales. Much in the same way that the loss of hanging signs and the development of new printing methods marked key milestones in the history of collectable cards, this too marks another milestone in the development of cards as we know them today.

Building on the existing collectability of trade cards, manufacturers that inserted cards into their products saw a very positive response from the public. Whether it was tea, chocolate, bread or of course tobacco, countless millions of cards rolled off printing presses around the world. From the 1870s onwards, many Victorians used these images to create elaborate and decorative scrap books of images by gluing them into albums (Howsden, 2000). In a pre-internet, pre-television and pre-radio era, these cards soon became a primary medium through which images of stage celebrities, animals and birds from around the world, military leaders, sporting figures - and practically any other subject that captured the public imagination - could be presented to an enquiring audience. Between 1870 and 1939, companies selling a wide range of products around the world capitalised on this phenomenon. Of all the products that issued cards though, we could argue that tobacco in particular led the way.

Cigarette Cards

In the case of tobacco, the insertion of a card was initially borne more out of necessity than to increase sales. Soft paper cigarette packets left the contents vulnerable to damage, and so a ‘stiffener’ card was included. These early cards often featured sepia photographs or woodburytypes of leading actresses, politicians and celebrities of the day. Thus, the size of the cigarette card in particular was dictated to a great extent by the size of the packet that it was inserted into. 19th century Allen & Ginter cards for example are seen in small sizes (c.68 x 37mm) from packets of 10 cigarettes or larger (c.82 x 72mm) for packets of 20.

In a similar way to the Victorian trade cards, these cards were in turn sought after by the public. For many it was a key way see other countries, exotic animals or soldiers and medals from around the world. One early collector is reported as saying that the late 19th century was a time:

...with no newsreels, no roto sections, no picture newspapers. A good cigarette picture was no mere plaything for a boy. It was life (Jamieson 2010:17).

As with earlier trade cards then, these pictures were not ephemeral adverts of a product but something a little more significant – cards carried knowledge and information on wide range of subjects to millions of people at a time when literacy and education was far from universal.

James Buchanan Duke was one of the first to use images of leading actresses of the day to promote his cigarettes in shop windows, but it has been said that the format followed by nearly all cigarette cards the next 50 years was defined by Edward Bok in 1878. Bok is said to have picked up a cigarette card which had been thrown down in the street showing a picture of a famous actress of the period (such as the Duke example shown here) and noticed that the reverse side was blank. He suggested to the firm who printed the cards that if a 100-word biography were provided on the backs of the cards, describing the subjects pictured on the front, they would prove far more interesting. His idea was immediately adopted (Cruse c.1945:2), and cards with a picture front and an explanatory text on the back become the standard format.

By the end of the 19th century it had become commonplace for cards to be issued in series of 25 or 50 cards. By around 1900, issuers such as Ogdens began to issue hardback ‘slip in’ albums for people to store and display their collections, and albums in a variety of formats would continue to be issued as long as cigarette cards were produced. The size and format of cards remained largely unchanged for over a century and arguably set the template that the vast majority of cards would follow to present day.

During the 1920s and 1930s, cigarette cards in the UK became what might be termed today a ‘marketing phenomenon’ (Howsden, 2000). They were issued around the world in their millions. The once hard-backed albums became a more straightforward paper affair, and some of the cards were even issued with adhesive backs ready for sticking, rather than sliding, into an album (John Player & Sons and W.D. & H.O. Wills being leading exponents of this approach). This move by manufacturers to issue cards with ‘sticky backs’ illustrates a clear knowledge of the way the public kept and stored the cards. It was a move away from a scrap book of mixed advertisement cards and towards storing cards in sets.

The sheer volume of cards that were inserted into packets of cigarettes around the world, and the standardised sizes and formats that other products sought to replicate, meant that for many people all such cards were 'cigarette cards' - regardless of whether they had been issued with cigarettes or not. Even today you may find people calling any card measuring the standard c.67 x 36mm a ‘cigarette card’, even though it may have been issued with tea or chocolate.

A common question is ‘when did they stop being issued?’, or indeed ‘why did they stop being issued?’. The answer is very simple. In 1939, as war broke out across Europe, Britain experienced significant paper and cardboard shortages. Issuing cigarette and trade cards in their millions became untenable, and so production ceased; indeed if we list all the series by tobacco companies based in the UK they stop unanimously in 1939. While during the 1950s and 60s tea and bubble gum companies did issue insert cards (particularly Brooke Bond and A&BC Gum), cigarette cards as we knew them were never issued on any significant scale again.

Commercial issues – trading cards

In the decades from the 1970s to present day, the cards we see are predominantly those produced and sold as collectables in their own right. We could argue that today is the age of the ‘trading card’, as cards are seldom issued with other products anymore (although this does still occasionally happen).

Some of the most popular sets from the history of cartophily have inspired new generations of similar sets. Despite cards no longer being issued with packs of bubble gum, there are thousands of baseball cards issued every year as commercial issues (indeed thousands may be an understatement!). The 19th century American tobacco firm Allen and Ginter – famous for being one of the earliest issuers of cards as well as having produced some of the most beautiful and highly collected cards in the hobby – has been resurrected in name only to issue cards of a similar design to one of their most famous sets of the late 19th century (see ‘Champions’ Burdick Ref: 28). The famous ‘Mars Attacks’ cards issued by Topps is still being added to with new artwork and sets that both expand and pay homage to the original set.

Many modern trading cards are simply series of images from film, television, the world of sport, etc - in fact, in many ways their format and theme is no different to their predecessors a hundred years ago (albeit larger and printed using modern methods). Some, however, are designed specifically so that collectors can play a card-based game with them, and so have another dimension to trading card collecting – Collectible/Trading Card Games or ‘CCGs’ / ‘TCGs’. We know that children did play games with cigarette cards in the 1920s and 1930s - although unlike their earlier counterparts, modern games use the information printed on the cards, rather than physically using the cards to flick at others! Pokemon would be good example of the latter type and more recently in the UK Topps’ Match/Slam/Hero Attax. Perhaps the most widely recognised CCG is Magic: the Gathering (MTG) (a topic that has websites, apps and forums dedicated to it across the world!). We could write books on each type of card, but since as this is an introduction we’d recommend looking online at some of the sets mentioned above for more information.

So, while cards inserted with another product to incentivise sales still do appear, they remain rare. Trading cards however are issued in their millions around the world and their appeal is still seen by both young and old collectors alike.

It may seem strange to see 18th century engravings next to modern trading cards. However, we hope you will agree that although personal taste will govern what you are drawn to and collect, all cards share common roots and are worthy of study and time.

References

- Bodleian Library (2001) ‘A Nation of Shopkeepers’, Article online at - http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/johnson/online-exhibitions/a-nation-of-shopkeepers

- Burdick, Jefferson R. (1960) ‘The American Card Catalog: The Standard Guide On All Collected Cards And Their Values’ (Pennsylvania: Kistler Printing Company)

- Cruse, Alfred J. (c1945) ‘All About Cigarette Cards’ (London: Perry Colour Books Ltd.)

- Heal, Ambrose (1925) ‘London Tradesmen’s Cards of the XVIII Century’ (London, Batsford)

- Howsden, Gordon (2000) ‘Introduction’ in ‘The World Tobacco Issues Index – Cartophilic Society of Great Britain’

- Jamieson, Dave (2010) ‘Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession’ (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press)

- Laird, Pamela Walker (2001) ‘Advertising Progress: American Business and the Rise of Consumer Marketing’ (Baltimore, MD: JHU Press)

- Malcolm, James Peller (1810) ‘Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London During the Eighteenth Century; Including The Charities, Depravities, Dresses, and Amusements of the Citizens of London, During That Period’ (2nd Edition, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme)